By Festus Adedayo

Bala-blu-blu-bulaba, All Progressives Congress (APC’s) festival of incoherences, should attract a writer. So also the celebration and justification of its impending fatality. Feeble and laughable as it may seem, Festus Keyamo’s Ananias and Saphirra role in this frightening reality too should not escape a dissection. I would have loved to ask Keyamo, in the words of Peter Tosh, “Where are you gonna run to” on judgment day? However, about the time of this meaningless waffle, I was presenting a paper entitled Between Ayinla Omowura and Ayinde Barrister: Conflicting Notions of Superstardom in Fuji and Apala Music at the African Studies Association (ASA) conference which ended yesterday. It was held in Philadelphia, United States.

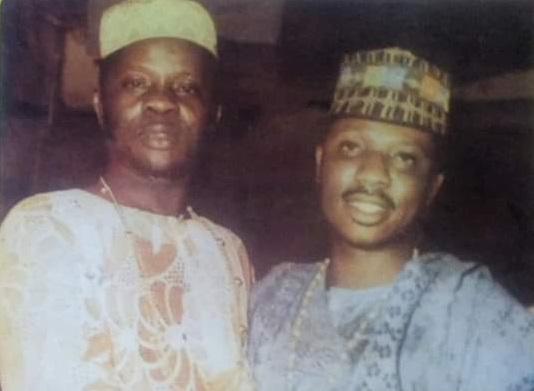

You will recall that I began the discourse on the theme of that paper in my piece of December 20, 2020, which I entitled Ayinde Barrister: In memoriam of a musician who peaked by Ayinla Omowura’s graveside. Permit me to share my abstracted arguments and submissions at the conference, after defrosting the paper of its academic niceties, below:

The death of Ayinla Omowura, a popular Apala musician, in 1980, is a watershed in Yoruba popular culture. The vacuum left by his demise could not be filled by any other Apala artist. Rather, another artist, Sikiru Ayinde Barrister, who played a different genre called Fuji, rose to the limelight from the shadows of invisibility. This presentation places the careers of Ayinla and Barrister in perspective. It engages with major economic transformations in the 1970s and 1980s in Nigeria which aided the rise of these powerful artists and the musical genres they played. The creation of superstardom in the art cannot be separated from contrasting notions of “good” and “bad” and “new” and “old” music. This problematic schematization of sound and art played a significant role in the rise of these two artists and the public politics built around their personalities.

Stars are creations of the media and their audiences are called fans. Stardom or superstardom is worthy of study because it has a cross-cutting relevance and implication for society. Indeed, musicians are linked to the social health of society and have a sweeping hold on the public sphere, so much so that they compete for attention with politicians and statesmen.

Ayinla Omowura and Ayinde Barrister (born Sikiru Ayinde Balogun) attained superstardom images in their respective genres among their Yoruba people. Their audiences constructed different and differing natures of the worth of their stardoms. While Omowura was arguably one of the foremost and most original musicians to sing the indigenous musical genre of Apala in Yorubaland, Barrister pioneered Fuji, and both shared stardom at about the same time.

In his creation of the Fuji music genre and taking it to the height it currently enjoys in popular culture music in Yorubaland, Ayinde Barrister made a mastery blend of existing traditional musical genres that ranged from Apala, Sakara, Awurebe, and others, making them into a fast-paced, danceable and modern genre. He projected the traditional African values of the Yoruba, and their daily struggles against life’s forces and in the same vein captured the attention of a modernist world which looks out for racy, entertaining music, Ayinde Barrister is reputed for his unexampled creativity.

Ayinla Omowura was bohemian, profound and unarguably, one of the most original Yoruba musicians of post-colonial Nigeria. He was highly talented and between the period of his superstardom, 1970 to 1980, and the time he got killed in a barroom brawl, he straddled the musical scene of western Nigeria and the west coast like a colossus. Using dense imageries, literary allusions, proverbs, and wise sayings, Omowura constructed sceneries that loom large in the subconscious of his listeners. Imageries of animals, human engagements and the blacksmithry where he once worked with his father, Yusuff Gbogbolowo, were deplored with relative ease in his songs.

Ayinla was apparently aware of the talismanic hold of his superstardom and the awesome powers of his talent. He flaunted these in the face of his musical traducers and competitors. This mastery of the geography of music and his flaunting of this understanding verged on arrant arrogance which rebounded on many of his contemporaries. This probably got him relentless combat against a string of enemies which even a combination of a thousand people would probably engage in their lifetimes. Yet, Ayinla was diffident and confident about conquering them all. His confidence was in his unique talent and in the talismanic powers of African traditional medicine.

While they were both reputed for their contributions to popular music and traditional culture in the southwestern region of Nigeria, scholarly arguments have ensued on the comparative weights of their individual stardom. The arguments began while they were both alive but it has outlived them at their passing. It was developed by their fans, out of engrossment with their talismanic and prodigious musical enchantments that still endure. More than four and one decades respectively after their departures, the most recent of the theses on their stardoms is that if Omowura, who pre-deceased Barrister, had not died, the stardom of Barrister would most probably not have had the sweeping hold it had on the dancehall for three decades before his own passing.

Of a truth, Ayinde Barrister, between 1980 when Omowura died and 2010 when he eventually passed as well, garnered a huge contemporary audience than Omowura probably gathered in his lifetime. Both of them rose to stardom in the period of Nigeria’s immediate post-civil war era beginning in 1970. It was a time of economic boom which came after the discovery of oil in abundance in the country. The petro-dollar craze in Nigeria at the time resulted in an era where there was a stampede by virtually all sectors and individuals to take a bite of the perceived surplusage that was touted in the Nigerian economy. It was also a time that witnessed an upshot in the craft of popular music. Musicians were forced to also engage in major economic transformations during the period of the 1970s and 1980s to ply their trades. The economic boom of this period, in no small measure, aided the rise of these powerful artists and the musical genres they played.

Their fans were the first to decipher the geography of consent and dissent from darts thrown at live music gigs and then smelled a mutating tiff between the two musicians. Omowura, however, burst the bubble in an album entitled Omi Titun (Vol.17) and laid bare the supremacy battle between him and Ayinde Barrister.

In a track of the album, he first began by cloaking who the subject of his harangue was. A man known for his cantankerous musical darts on his musical adversaries, He sang: Ayinde, ma je ki n gbo/ pe mo ji e l’orin lo/Ko je je be, oro apara ni…/E ma de ma gbe’ra san’le ni’waju iru wa/To ba se pe e gbe’raga ni iba san/A nroju je’ko obun lowo/Obun lohun nse fuji ni’gboro/O nf’owo y’okun, okuta nbo/Eyin ko mo pe, ka to p’elede, ese a pe/Ka to p’aja, ese a p’egbeta ndan?/Eni ba fe wo’le odu, a se’tutu…

Translated, it read, Ayinde, perish the thought that I stole a line of your song/This allegation cannot be so; it smacks more of a huge joke…/Don’t pump up a non-existing ego before a musician like me/If you really want to articulate your supremacy over me, say so for the world to hear/I merely honoured you by taking a sip of what belongs to you/Just like sharing a bite from a meal in the hand of someone sworn to a life of filth/This filthy Fuji musician now announces his worth and supremacy to the world by reason of my condescension/Don’t you know that music is like a coven and anyone who desires to share the dais with us will make sacrificial offerings?

In the same track, the next stanza saw Omowura going rather frontal, with an effusion of acidic diatribes against the said Ayinde. He sang: O fe je soda ni’le orin/Ayinde, o fe je soda ni’le orin/Ohun t’enikokan ki je laye/Eni to yo, to npanu e nile orin/Eni ti o yo lohun o ran’kun/N’isoju ojogbon, se lo mi a be…

Translated: He really wants to commit suicide on the bandstand/Ayinde wants to swallow a soap/A deadly poison that no human being who values their existence will ever contemplate/That move is comparable to someone going beyond their reach/The end result will be cataclysmic.